So, how do you follow up one of the most critically acclaimed rpgs of the early 90’s? You do it by taking what made it work, improving on what didn’t and streamlining the rest of the game in an incredible package. Those who know my opinions and tastes know that I consider Phantasy Star IV the greatest rpg of all time. I mean that as purely as I possibly can. No embellishments, no hyperbole, nothing like that. Obviously others will disagree with me and that’s fine, there’s a good amount of competition for that title. Final Fantasy 6/7, Chrono Trigger, etc. But for my money, PSIV trumps all of them, and I’m here to tell you why.

After the disaster that was Phantasy Star III, the Phantasy Star crew took a break from the main series, occasionally producing a side-game or two that would remain stuck in japan (Though each of these games has fan-translations). However, it was in 1993 (’94 for us Americans) that the Phantasy Star team brought the final chapter of the Phantasy Star Saga to the Sega Genesis. Now, you may be asking “What happened to III? Why are we skipping to IV after II?” That’s because III is a misleading title. It’s not so much as the third game in the series as it is a side-game. If you want to get into specifics, III technically takes place after IV does, so I feel there’s no reason to do III before IV.

Phantasy Star IV takes place 1000 years after the Great Collapse (The event in which Rolf disabled Mother Brain, destroying most of the advanced technological culture in PSII). Over 90% of the Motavian population died as a result, but it was ultimately for the greater good as the people left managed to salvage what was left of their culture and move on. Motavia has now reverted from the terraformed green planet Mother Brain shaped it into, back into the desert wasteland players from the first game will remember it as. No longer is Mother Brain controlling the world and its population, the people are generally free to do as they will and there’s hardly anything in the way of an established government in this world. Remnants of the advanced technology used over a thousand years ago do still exist, even if it’s nowhere near as prevalent as it was the prior game. Because there’s little in the way of government, a Hunter’s Guild has opened up to deal with the chaotic and rampant monsters that run throughout Motavia. The game starts proper with the hunters Alys and Chaz as they investigate a monster disturbance in a Motavian academy.

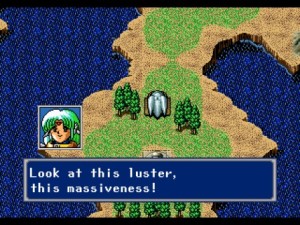

Now, there are a lot of different things that immediately come to the surface with Phantasy Star IV. One thing, the game’s presentation is a lot better than II or III. Instead of simply having character sprites kind of bounce around when talking to each other, PSIV has manga style cut scenes. They’re structured something like a comic book, allowing the player to see each character’s reactions. This is a significant difference from seeing a few sprites pop up a dialogue text and makes the game and the exposition feel a lot more engaging. Another new feature is the inclusion of a party chat feature. I don’t know the specifics of which game introduced it first, but it’s a pretty neat feature to include in the game. It adds little bits of colorful dialogue to the game and lets the player know exactly where they need to go next. It doesn’t detract from the game at all and is completely optional, but adds functionality and intuitive design to the game, which is always a pleasant thing for me.

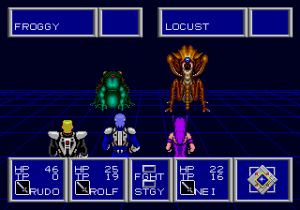

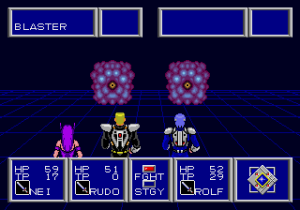

Combat and character-balance are two features that Phantasy Star IV improves greatly upon from II. Returning from II are techniques, except this time the TP pools characters have to draw from has expanded greatly, more than enough that a player can reasonably feel comfortable using their techniques in random battles without much worry. Far too often a player in PSII had to intentionally hold back from using techs except in extreme circumstances because the characters simply had pretty limited amounts of TP to draw on. This is fixed here, and it’s all for the battle now since combat is a lot more entertaining instead of something a player has to trudge through just because. Another addition is the inclusion of Skills, which work similar to magic charges from Final Fantasy I, but with a larger pool of charges to work with. Like with TP/MP, the amount of charges a player gets for a certain skill increases with each experience level the player accumulates. This allows for more variety in what characters can do without devolving to the point that every character can do everything, as can be the case with some other rpgs. One more addition to the battle mechanics of Phantasy Star IV is the inclusion of combos. If two or more characters use the proper techniques/skills in the correct order, they can use a more powerful combination technique. Unfortunately, it has to be done as described or else it won’t work, just as any enemy can potentially interrupt the combo by taking their turn in the middle of it. Fortunately, PSIV’s designers sought a work-around for this issue in the form of Macros. A player can pre-set a number of Macros so each character will take their pre-set action, and the player can even choose what order they will act in. This means the turn order can be precisely manipulated so that the proper characters can act in the order desired and so that an enemy will not interrupt them. It’s a brilliant mechanic that definitely should have been included in many other rpgs after this game was released, but unfortunately wasn’t. I hope many game designers look back to this game and realize the potential that this mechanic has and repurpose their games with it in mind.

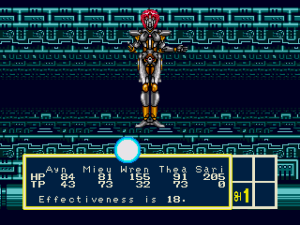

In regards to character balance, almost everyone is useful in some capacity. Both Chaz and Alys right from the get go establish their positions in combat rather readily. Alys serves as a jack of all trades archetype whereas Chaz is more of a Magic Knight subtype. Later on come characters such as Hahn (who fills the role of “Black Mage” in the early goings) and other characters fill more niche but necessary roles within the party. There are two androids Demi and Wren (Who function by being able to be unaffected by standard healing items/spells but have their own healing powers to compensate) and Gryz (Who is a bruiser with high attack power and HP that can take a lot of hits for the party). Then there’s Rika who has the best experience growth as well as combining high attack power, speed, lower tier healing spells and buffs. Raja carries all the high-tier healing abilities but is relegated to that role, Rune replaces Hahn for the “Black Mage” archetype and is much more efficient at it, and finally Kyra who at late-game combines the magical utilities of Rune and Alys’ jack of all trades mentality. Each character comes into the game appropriately leveled, so that the player never needs to have to grind experience levels in order to keep them even with the rest of party. The designers also intelligently took care to make sure their equipment is always on par with the rest of the crew, making it so they didn’t need to constantly purchase superior arms once they had joined the party. As well as keeping each character balanced into their fixed role, this keeps the player engaged with the game at a fast pace, never having to spend time forever in once place to be assured that he/she can finally progress further.

Unlike Phantasy Star II, IV has a revolving door of characters that make up its cast not at all unlike Final Fantasy IV. Some stay for very short periods of the game whereas others are involved for the duration of the entire game, primarily the “Big Four” of Chaz/Rika/Rune/Wren. This is particularly good, as it allows for a wide variety of cast without focusing so much so on one individual character. Some detractors would argue this is to hide a weak cast, but I vastly disagree with that sentiment as the same technique has been used in other video games and other mediums to great effect! In a plot whose focus is more centered on pacing, dragging things out in regards to character development would be a blow to that setup, and I still feel that PSIV’s characters are entertaining enough to merit their existence. It isn’t as though they have absolutely zero depth at all and given the technical restrictions of previous games in the series they undoubtedly have the most character development in this game compared to all others. The central idea behind this plot over character development dichotomy is flow, an important concept integral to PSIV. In a tightly composed and efficient experience, being able to flow quickly is something extremely important to the feeling of the game. And this is precisely what makes Phantasy Star IV so enjoyable as an experience.

Phantasy Star IV, is quite obviously a video game. I don’t think anyone can possibly come up with a more obvious statement. As such, it conforms to the standards of what a video game is. What PSIV isn’t, is a movie or book. And it’s perfectly okay with that. Unlike movies or books, characterization and writing are only a small piece of the puzzle for a video game. There’s gameplay to figured out, dungeons to arrange and one needs to figure out how the plot fits into the game both literally and thematically (Or else what’s happening between gameplay and plot feels disconnected and inorganic). There’s an actual game that needs to be played. For that, it only makes logical sense that a plot within a video game would lean towards being fast-paced action with some witty lines and charming moments thrown in. It works in a video game because it tailors perfectly to the medium itself. Some other games spend disproportionate amounts of times in a vain attempt in fleshing out the worlds and characters that inhabit them, and yet I don’t think that in of itself is not an inherently bad thing to do. There are strengths to assuming that style of narrative but I don’t think it’s conducive to the format of a video game and fits a book or movie more readily. It’s merely inefficient which is PSIV’s greatest strength, is that it’s such a tight and efficient experience.

In terms of setting and tone, Phantasy Star IV is both a logical extension of II and a bit more welcoming in comparison. Motavia has reverted back to its desert wasteland from PSI, but in exchange is nowhere near as dark and moody as PSII felt. The tone of Phantasy Star IV is less serious, and more charming and whimsical than any other in the franchise and I think that’s a decision that’s all for the better. In the bitter and often depressing atmosphere of Phantasy Star II, the player was left to defend for themselves in equally harsh dungeon designs and enemies to fight. In PSIV, the difficulty of the combat and dungeon layouts has been significantly reduced, all for the better. No longer are random encounters so difficult as to threaten to wipe out the player in two rounds or less. Neither are the dungeons so massive as to leave players confounded on how exactly to progress. That isn’t to say that they’re so brain-dead that a child could clear them no problem, but it finds a nice and solid middle ground between masochism and simplicity. Combat has a lot of variety with each character’s abilities and yet isn’t watered down due to everyone having too much variety in their powers. Each dungeon usually has one specific element to it that makes it unique in some fashion, keeping the experience fresh. Too often, rpgs result to a copy-paste mentality in dungeon design. There are usually three to four unique dungeon gimmicks or designs are stretched out and reused a number of times, which can make the experience feel a bit stale. It is because of this, that the uniqueness of PSIV’s dungeons help keep this game feel like it’s aged much better than some of it’s peers have.

One aspect of PSIV’s combat I adore is the amount of options given to the player without handing them absolutely everything. Elemental weaknesses, healing, instant death, buffs and attack-all abilities are all useful in varying situations, keeping combat interesting over the haul of the entire game. For rpgs, that’s a critical component, as rpgs tend to be lengthier than other genres of video games. Basic gameplay needs variety to sustain player interest over a longer period of time, after all. Platformers, shooters and puzzle games don’t have this issue as they are shorter games. Even rpgs as early as the SNES/Genesis era could last as long as 20 or more hours, easily worth multiple playthroughs of a much shorter game. Phantasy Star IV is on the shorter end of the stick when it comes to total playtime (Usually around 12 hours), but I feel these points help illustrate how well paced PSIV is. Pacing is an important thing in video games, as it helps us keep our attention on the game for the long haul. I’ve played numerous games that bored me or I simply quit because the pacing was mediocre and my interest simply could not be sustained. Pacing in an rpg has to do not only do with keeping the basic gameplay elements interesting, but by making the plot interesting and introducing new plot elements at a reasonable pace. Not too fast to leave the player confused but not so bogged down in details the player may not care about.

Phantasy Star IV’s plot, for better or worse is a really fast rollercoaster ride. The manga illustrations breathe a life into the game not seen in other rpgs, and most cutscenes don’t take very long to get through but have enough meat to them to satisfy the player. Combined with the party chat that pretty clearly tells the player where to go next, PSIV always moves full steam ahead. Like PSII, the structure of the game is fairly linear though PSIV adds minor touches of non-linearity to the game. The plot progression is still done in a linear manner, but an occasional out of the way town or extra dungeon with no bearing on the plot will appear along the way, usually bearing some reference to a prior game in the Phantasy Star franchise. PSIV is chock full of these references throughout the game, mostly to the first two games in the series but there is one reference to PSIII, though it’s entirely optional. These references are merely for the player who is already invested and interested in the Phantasy Star franchise as a whole, but the game keeps itself fairly self-contained so recognizing them isn’t really necessary. This serves to make PSIV a lot more accessible, easy to pick up and play even if the player doesn’t know what happened in PSI and PSII. Some minor worldbuilding details are missed and some references forgotten but in the end it’s not a huge deal.

Musically, PSIV has taken strides even beyond what PSII achieved. PSIV returns with PSIII’s composer but manages something far better than PSIII’s soundtrack. PSIII suffered from very poor sound quality due to it trying to go for an orchestral type of soundtrack for an early 90’s rpg. It just wasn’t gonna work, whereas PSIV works within the limitations of the Genesis chip and puts out some of the best tunes on the console ever had. PSIV’s soundtrack ranges from catchy and upbeat to chaotic and atmospheric when necessary. For example, the random battle and boss themes are catchy but have enough variety that they don’t get old too quickly. The final boss theme starts out extremely atmospheric and foreboding but quickly segues into a blast of chaotic riffing. There are moments in the plot in which can best be described as tender and the music follows suit, as well as moments that are uplifting and the music properly matches those moments. There are even some remixes, such as the dungeon themes from PSI being remixed in this game. The instruments are different, but they’re still recognizable to players familiar with that game, bringing not only more references from previous games but adding to a sense of finality and closure to the last game. These are all effects that bring a greater sense of engagement to the player, especially if they’ve played each game up to this point.

But don’t just take my word for it, have a listen for yourself. Hell, have another one on me!

Now I am going to go for a proper dissection of PSIV’s plot. Since this is an in-depth plot analysis, I am going to indicate that if you do not want plot spoilers to skip the remainder of this review. However, if you’re curious about the plot, feel free to continue reading on.

The plot of Phantasy Star IV may not be its most standout feature compared to it’s robust and excellent combat system (Though it certainly isn’t its worst feature), but that’s merely due to the game’s tight structure and lightning fast pacing. If nothing else, PSIV’s plot is entertaining on its own merits while using the strengths of the series’ continuity to add an extra dimension to the game. Unlike I and II, whose plots were fairly bare-bones, IV has a meatier story going for it, without resorting to bogging the game down with unnecessarily long cut scenes. Basically, what Phantasy Star IV does it does really well and its that it emphasizes pacing over in-depth plot.

Like I mentioned earlier, the plot of PSIV starts with two hunters Alys and Chaz investigating a monster disturbance in a Motavian academy. It’s soon after they take this job that the player is introduced to Hahn who desperately wants to join the duo. Alys agrees, but only for a payment of money. This is somewhat of a running gag through the early sections of the game, with the price Alys demands increasing each time. What’s interesting is that the player actually receives the money from each of these moments. It’s not anything major, but attention to detail is something that Phantasy Star IV executes flawlessly and this is another example of it.

At the Motavian Academy, the two Hunters Alys and Chaz receive a job to deal with the growing numbers of monsters that exist in the basement of their facility. What’s immediately noticeable is that Alys instantly picks up that there’s something shifty going on, indicating her intellect, instead of blatantly trusting their client just because. Especially with a flimsy excuse given to them as to what is going on, it showcases that the heroes are actually competent and not naive children that tend to dominate the casts of rpgs. As soon as the duo prepare to infiltrate the basement, an assistant to the client, Hahn asks to join the group. Alys decides to let him join, but only for a fee. She continues this process throughout the game, becoming something of a running gag, showcasing Alys’ ruthless intellect while at the same time keeping a lighthearted mood about the whole situation. Its a very humorous thing and mostly played for laughs.

With Hahn added to the group, the party uncovers the source of the trouble in the basement and refers back to the principle. Who in turn starts to explain what is going on, which introduces Zio as the game’s early villain. As it turns out, Zio essentially blackmailed the principal to keep his trap shut about various nefarious things happening in the part of the world known as Birth Valley. The group sets out to trail Zio and figure out what exactly is going on with the world. More information on that comes as soon as the party gets to Birth Valley and finds everyone in it completely petrified. The immediate goal now shifts to finding a cure for everyone afflicted by this incident, which leads the group to find a man named Rune, who turns out to be an old friend of Alys (There are implications that there is more to their friendship than meets the eye, but that’s never really put into focus in the plot). Rune then also joins the group, which brings about an interesting gameplay change. As players will undoubtedly notice, Rune is well above the level curve for this point of the game, which leads to a lot of interesting possibilities for the short amount of time he’s in the game. His abilities for one are clearly a step above what the player is used to at this point, so this encourages a lot of experimentation with techs/skills and the like. This is a good thing, as Phantasy Star IV’s combat is complex enough to really encourage making use of that experimentation mindset.

The town in which the player actually finds Rune is completely in ruins, apparently obliterated by Zio before Rune had ever gotten there. The fact that the town is already in the shitter gives us two clues about Zio. One, that he works faster than the party does and two, he’s a threat that needs to be taken care of. Both of which are very good traits for a villain to have in order to establish both relevance and threat. There’s an immediate goal to be considered, outside of the influx of monsters plaguing the land, which lends more credence to PSIV’s philosophy of moving the game at a blistering pace. What’s even more interesting is that in a previous town of Mile, Zio’s Castle is clearly visible across a currently uncrossable passage of quicksand, yet the heroes are unable to make their way across it for the time being. It reminds me a bit of how LaShiec’s Castle in PSI was way out of the player’s reach and yet it was still known as a clear goal. Eventually the player will be able to make it there, but it serves for a good reminder of the future goal and makes for good foreshadowing.

Soon after making their way to a future town, Rune leaves the group but it replaced by the likes of Gryz as Rune has other things to take care of while still pointing the party in the right direction. Gryz certainly doesn’t have the utility that Rune had in combat, but he fills the big bruiser role in a more than adequate fashion. This also starts a turning point where many characters in Phantasy Star IV start coming and going at different points in the story. Only a small handful are permanent fixtures in the party, though most characters do return at one point or another. This is also important for gameplay reasons since that means the usual party setup is never a constant but always changing. Since Rune is out, the party now lacks the character who had all the multi-targeting techniques and skills all of a sudden in lieu of a melee centric character with slightly better defenses. It’s a subtle change to the game mechanics, but it’s a very effective way of changing up the game so combat is an ever changing force within the game, never stagnating or remaining still.

With Gryz in the party, the group is lead to the cure for the petrifaction in Birth Valley and quickly undoes the effect Zio had on them all. This opens up an area in the back cave of Birth Valley that’s essentially the first major dungeon of the game (The player had gone through a small number of smaller dungeons prior to this, but for the purposes of this review I don’t consider them “major dungeons”). At the end of the Bio-Plant the party runs into Rika who promptly joins the party. To those unaware, Rika is essentially a continuation of Nei from Phantasy Star II. She carries a similar appearance while still maintaining her own unique charm and identity. However, things are a bit different this time around. I mentioned in the Phantasy Star II review that Nei represented the bridge between technology and nature and Rika is no exception. However, Phantasy Star II also had a very cold and distant atmosphere to it so it made sense that the two concepts couldn’t be properly linked. Phantasy Star IV though, is nowhere near as harsh and unforgiving. To the contrary, PSIV is fairly lighthearted and has a very warm and welcoming atmosphere. Then as you expect, Rika has a much easier time fitting into society (Or what’s left of it) than Nei ever did. Whether or not that’s a deliberate design choice is up for debate, but I like to imagine that represents the world being able to accept a more radical concept like a biological half-breed like Rika. It leaves a very positive image and works well within the framework of PSIV’s plot and atmosphere.

With Rika along for the ride, the group learns of new developments, specifically the kinds of developments that threaten the livelihood of their beloved planet. “Seed”, the computer controlling everything about the Bio-plant reveals that the system (That is, the system adding life-support to Motavia) is unleashing lots of monsters into the wild and is currently beyond its control. If nothing is done, the ecological climate of Motavia will be in serious jeopardy, eventually leading to its destruction. The solution to this problem then becomes to shut down every identical system in Motavia, a surely tedious task. However, it seems that only Nurvus (Since it’s the one that supplies energy to each system) needs to be shut down for the betterment of Motavia. However, Nurvus can only be shut down by an android named Demi, who is currently held hostage by Zio. So all in all, it seems a confrontation with Zio is absolutely inevitable no matter what. Finally, Seed acknowledges that Rika is a product of one thousand years of genetic information (If that didn’t make sense, she’s Nei’s successor) and allows Rika to depart with the party. Soon after, the entire building collapses after a self-destruction (Most likely done intentionally by Seed to circumvent the system from making more monsters). Now I think it’s time to discuss Rika at length, because she is quite a powerhouse. Her level starts at one which may lead more experienced RPG veterans to be wary, but that is not the case here. Rika’s levels advance extremely quickly due to her low experience curve and have a multitude of unique abilities. At this stage of the game she’s clearly the game’s best healer, has access to useful buffs and has a very reliable physical attack to use. All in all, she’s without a doubt one of the most well rounded characters introduced to the game thus far and never really leaves the party despite others coming and going so often which helps make her one of my favorite characters in the game.

In the next few towns the player encounters, one of them exists near an abandoned spaceship that clearly crashed into Motavia’s surface. This dungeon is completely optional, but it gives a bit of information about Phantasy Star III in it at its conclusion. This is the only point in the game which has any kind of relation to PSIII at all, which is a good thing as far as I’m concerned. It should be noted that this part right here is optional. Now, what makes that such a big deal? In Phantasy Star III, the town that explained PSIII’s relationship to the rest of the series was also completely optional though in that case that information was a lot more crucial to understanding what was going on. In PSIV, the events of PSIII are largely irrelevant so this is a non-issue. I find it curious that both games use the same tactic, but PSIV’s execution is top-notch so it doesn’t detract either from the plot or the gameplay. In PSIII though, the execution leaves a lot to be desired, and so it becomes a detriment to that game. This really showcases the differences in execution between these two games and why I really like one while I loathe the other. Next up is the town of Aiedo, which serves as the general hub for all things on Motavia in PSIV where the player can decide to do sidequests. Sidequests are done via the Hunter’s Guild, which can be accessed as soon as the player gets to Aiedo and has no other restrictions. Various quests are posted in the Guild, and the player can choose to satisfy them for a monetary reward, or ignore them entirely. As the player progresses through the game, they’ll unlock more quests to undertake. PSIV doesn’t have too many sidequests, but of the ones it does have are pretty entertaining and give a bit of backstory to the world of PSIV. All in all, I approve.

(Why Chaz, it’s the stench of failure that emnates from Phantasy Star III!)

Before the crew finally gets too Zio’s Castle, there’s an odd little town right next to it. Unsurprisingly, the entire town is composed of people who are into Zio’s cult religion. I personally like this little touch because it shows what Zio’s been doing over the world. He’s been trying to expand his influence and empire, and not just sitting on his throne. It also gives the player another incentive to stop him so that they can stop the influence of his cult. It’s a small touch but I think it’s one that goes along well with all the other touches PSIV offers. There’s also an additional sidequest in the Hunter’s Guild later in the game that revolves around this cult, for what that’s worth

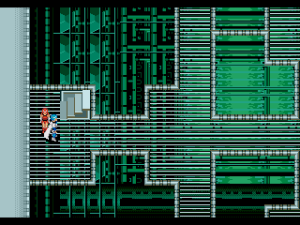

The first thing the player notices as they enter Zio’s Castle is that there is a basement section that’s completely sealed off for the moment. The player will be able to access it at a later part of the game, but it gives a certain sense of foreboding to it. “What’s exactly in that basement?” the player might ask to themselves. That’s for them to figure out down the road once the plot calls for it, but adds a kind of foreshadowing and makes the lead up to that part of the dungeon interesting. This dungeon also features some unique techniques in dungeon design. There are sections where the view appears to be from the side instead of top-down (It isn’t, it’s just the perspective that makes it seem that way). It’s nothing special but it does make the dungeon seem a bit more unique that way and as far as aesthetics are concerned it’s a neat trick. At its conclusion, the dungeon ends with the crew finally finding the android Demi. Unfortunately, Zio has no plans to allow his android to escape without a fight. Enter the first “major” boss fight of Phantasy Star IV, and it’s an unwinnable one. After 3 turns the fight automatically ends with Zio dealing major damage to Alys, causing the party to retreat (But manages to keep Demi with the party despite their failure).

What’s interesting about this segment is that it becomes clear that Zio is a pawn to Dark Force, the true antagonist behind PSI and PSII. Statues emblazoned with Dark Force’s face are littered throughout Zio’s Castle, alluding to that upcoming plot point. It’s pretty neat foreshadowing on PSIV’s part. Dark Force even appears in the background of the fight against Zio, if that point wasn’t clear enough already. For those familiar with PSI and PSII this simply means PSIV is a continuation of what we’ve seen before: Dark Force trying to destroy Algol once again. With regards to PS veterans, this should be obvious enough at this point which establishes the connections between I, II and IV. This helps since each game has their own style and feel (II and IV in particular contrast each other very heavily; one being rather cold and harsh and the other bright and welcoming). For those that didn’t play the first two games, then this is just a cool plot twist that they didn’t see coming but can appreciate after going back to playing the prior games. It’s this balance PSIV strikes between old and new players that makes it a really special game.

With Alys unable to recover, the party is left to assume another way to deal with the issues surrounding Motavia’s survival without her. Fortunately, Demi takes her place in the party so the group doesn’t lose a party member total. Demi’s introduction to the game is interesting because it marks the inclusion of instant death techniques. Unlike most RPGs where instant death is an afterthought due to exceedingly low hit percentages, PSIV has managed to balance out their use. Most instant death abilities are based on a specific monster type, and if they’re weak to it you’re basically guaranteed to kill them. If they aren’t weak to it then the likelihood of them being insta-killed is significantly lowered, so the player is encouraged to experiment and strategize. PSIV almost always lends instant death abilities to skills which are dictated by charges. Unless the player is disgustingly overleveled, they will likely only have a handful of charges with which they can use those instant death skills. This allows them to be useful but not overpowered either, which is an important distinction in combat and it’s a part of why I think PSIV still has some of the best turn based combat ever in a jrpg.

(Yes, that will never ever be taken out of context under any circumstances)

Without Alys, the next goal is to find Ladea Tower since it’s assumed that’s where the party can find Rune and have a much better shot at dealing with Zio if Rune joined them. This leads to Demi introducing the player to their first vehicle of the game, the Land Rover. Vehicles have been a part of the entire PS series (Even that game which we do not speak of) so for veterans this is no surprise. PSI had three distinct vehicles (Though only two were necessary for completion) and PSII only had one. This time however, PSIV changes up how vehicles are handled. While riding in one, combat is handled completely differently. The player is taken to a 1st person view of the cockpit with completely different mode combat. Instead of each character getting a turn, the vehicle uses various attacks it has at its arsenal instead and is treated as Skills are for the party. Vehicles have their own HP completely separate from what the party has, so that’s nice. Vehicles also move a lot faster than the party does (And the party wasn’t exactly moving at a sloth’s pace either) on the world map. With access to the Land Rover, the party has now what it needs to access Ladea Tower, but it’s also confirmed by Demi that the cause of what is going on with Motavia not only has to do with Nurvus malfunctioning but a space satellite named Zelan that is issuing abnormal commands. So even if the party defeats Zio, there’s more to do to ensure Motavia’s survival. This adds another goal on top of defeating the villain (which admittedly can seem fairly old hat), making the scenarios surrounding the solar system feel a bit more epic in scale other than just “beat the bad guy”.

At this point a few side areas open up (Notably the Plate System which has an optional Skill Demi can learn here) and Termi which serves as a giant reference point to PSI. Alissa from the first game is treated with reverence that she never had in PSII (I can only assume this means that ancient records that predate PSII were found) and even has her own statue to boot. It’s nothing special but is another nice reminder of the player’s accomplishments if they did play the first game, further cementing the connections between the three games.

Once in the Ladea Tower, the party finally meets up with Rune (Who incidentally enough, is evenly leveled with the whole party unlike last time where he was easily ten levels ahead of everyone else). With Rune in the group, the party finally has a five man party for the first time in the game. The group moves to collect the Psycho-Wand (Which apparently allows the party to actually damage Zio unlike last time). But before they set out for a rematch, they move back to check on Alys. Unfortunately, things don’t quite go as planned. Shortly after the crew reaches her, she dies. Despite the sadness inherent to this scene, I really like what this means for the characters. Alys was essentially Chaz’ mentor, meaning this is the point where he needs to think about himself and where his priorities lie. He no longer has his mentor to rely on anymore, no crutch to hold onto. This makes things more interesting as Chaz now needs to stand up and grow even stronger to not only deal with Zio, but the problems that plague Motavia as a whole. This is emphasized even further in the following cut-scene where Rune talks to Chaz about Alys and her contributions and what they mean long-term.

Hahn decides to leave the party, owing to his connections to the academy to help them out in some other way. Hahn eventually does return to the group at the very end of the game, but until then Hahn is but a fleeting memory. Regardless, with the Psycho-Wand in hand the group assaults Zio’s Castle one more time but this time they are not blockaded by the invisible barrier from before. This allows them access into Nurvus (The very same area from before that was mentioned). Unfortunately, they need to be in the very nucleus of Nurvus in order to do anything with it. Before the group reaches said nucleus however, they run into Zio one more time. The second fight against Zio runs differently than the first in that it’s no longer an unwinnable boss fight. Bear in mind that the player has to actually use the Psycho-Wand as an item in order to tear down Zio’s defenses that prevented the player from damaging him the last time (I thought doing so was obvious enough but I’ve heard comments from other players that they didn’t think to actually use the item on him, so I figure it’s worth mentioning).

As for what this boss fight means, I like it quite a bit. Being able to finally fight Zio for real after the illusionary boss fight before is rather satisfying (Especially after what happened to Alys) since the game doesn’t dick around with unwinnable boss fights. If used sparingly, they’re an effective means of making the player feel like they’ve accomplished something by conquering a tough opponent, but if they’re used too much then it feels very unsatisfactory and I consider that a negative when it comes to game design. Fortunately, PSIV is on the winning side of this dichotomy.

After the fight, Zio is killed but the party’s troubles aren’t over yet. Vengeance has been dealt with, but Demi is forced to leave the party so that she can effectively deal with Nurvus on her own. But as it turns out, Nurvus is only one of the systems that needs working with and the party will have to find other ways of fixing the other systems spread throughout Motavia, so their work is hardly done despite Zio’s death. The next target turns out to be Zelan, the space satellite mentioned earlier. Demi (assumedly) raises a previously underground space shuttle for the party to use so that they can contact Zelan and Demi’s master Wren. This is also the point where Gryz leaves the group since he doesn’t want to go leave the boundaries of Motavia for his sister’s sake, leaving the group down to a trio.

Once on Zelan, the party finally gets to meet Wren (For those curious, this Wren is different from the PSIII incarnation despite looking similar). Unfortunately, he reveals that Zelan has absolutely no control over the Motavia systems whatsoever, but the satellite Kuran that is responsible. Wren joins up, serving as the party’s tank for the remainder of the game (The rest of the game will see the Chaz/Rika/Rune/Wren lineup stay consistent with the 5th spot swapping in and out with the remaining characters). While heading over to Kuran, there happens to be a stowaway (assumedly provided by Dark Force) that attempts to destroy the ship they’re in. While the party easily crushes him, the pawn still succeeds in doing so, forcing a crash landing onto the planet Dezolis. Shortly after landing, the Dezolian priest Raja joins the group as well, rounding out to a party of five once again.

Before I advance further in PSIV’s plot dissection, let me make one thing clear. Dezolis is a hell of a lot more bearable in this game than it was in any previous game before it. No longer is there any bullshit mogic cap crap to deal with as in PSII or the separated tunnels that made PSI’s Dezolis a nightmare to navigate. It’s still cold and frigid, but it’s no longer a pain in the ass to deal with, so I am perfectly fine with that. With that in mind, let me take a minute to talk about Raja as far as combat goes. Raja is awesome. Normally White Mage/Priest archetypes aren’t the best characters in the game, but those characters aren’t Raja. Up to this point the healing capabilities of this party has been so-so. Not bad, but not awe inspiring either. However, Raja is a powerhouse when it comes to supportive abilities. His healing easily surpasses anything anyone else has had at this point, accurate instant death for evil enemies, and the only skill in the game that restores TP (Also note that Raja has insanely high TP growth and he’ll almost never run out). As far as healing characters in jrpgs go, Raja is easily one of the best.

The player is left to their own devices at this point, but the plot progresses after wondering through a few scattered towns over the Dezolian overworld into a hidden hangar. Inside the hangar is their next objective, the spaceship Landale (A PSI reference, since Alissa’s last name was Landale). Once in the Kuran satellite, it’s obvious that Kuran is very different from Zelan in that now the player has a full dungeon to navigate. It’s really nothing terribly difficult either, but what makes Zelan stand out is that at the end is Dark Force as the next major boss. Normally (And by this I mean PS I and II) Dark Force is the end-game boss. Since the player is only about half-way through the game at this point, that obviously isn’t the case here. There’s reasons for it, but if Dark Force is involved this early into the game, that’s obviously reason for alarm on the player’s part (Assuming they’re a series veteran, otherwise it doesn’t mean much to them).

What concerns the party is that now Kuran is working properly but the significant snowstorms are still ravaging Dezolis with very little explanation why. The party agrees to head back to Dezolis to investigate the matter further, while Wren unveals the Ice Digger, a vehicle that makes travel through the snowy weather more bearable. Like the Land Rover, combat in the Ice Digger works in a similar fashion except the Ice Digger is a tad bit more powerful – to compensate for the stronger enemies found on the Dezolian overworld. And for what it’s worth, the Ice Digger is another shoutout to the first game (Since the player had to purchase it in that game, where it’s graciously given to the player this time around for free).

At this point there are a few side-areas the player can divulge in (And doing so has its own rewards too). One such example is the Myst Vale cave. It’s essentially a giant reference to the first game (again) as it’s filled with Musk Cats (The same type of animal as Myau from PSI). At its conclusion, the player encounters an extremely large Musk Cat (Who is implied to be Myau, and it’s really obvious that it is). For the player’s efforts they receive the Silver Tusk. Ignoring again the obvious PSI shoutout, every single person who plays PSIV should make it a priority to collect this item as it offers Rika the ability to converge the holy element in her physical attacks. Since most end-game enemies are weak to holy, this is without a doubt a side-quest the player shouldn’t turn down.

Soon after making their way to Dezolis to further investigate the matter, the party runs into Espers (Lutz’ underlings from Phantasy Star II) trying to deal with the same black energy wave that ended up killing Alys. As a result of being exposed to it, Raja falls ill and is unable to proceed with the party, knocking the party members down to four once again. Fortunately, Raja and the others afflicted with the illness aren’t in as much danger as Alys was (Alys took a direct hit, where it’s implied the others have a much lighter version of it). The next goal is the Garuberk Tower which seems to be the only thing left which can be causing the dangers on Dezolis. As they do so, they encounter a young female Esper intent on getting through to the tower but caught up by animated trees that are quite violent. This leads to an interesting boss fight in one sense – that while the player can easily kill the monsters in the fight, they continually regenerate rendering the fight unwinnable. The monsters themselves will likely not kill the player though, leaving the fight a bit different from the unwinnable fight against Zio. The Esper introduces herself as Kyra and turns out to be the final “5th” party member in all of Phantasy Star IV (More on that later when it becomes pertinent). Kyra suggests that the crew head to the Esper Mansion to figure out how to progress into Garuberk Tower.

I want to take this moment to talk about Kyra’s combat potential, especially since she’s the final extra party member in PSIV. Kyra operates as sort of a fusion between Rune and Alys, being a jack of all trades offensively with a bit more of a magical focus. That doesn’t sound so hot on its own, but unlike Rune and Alys, Kyra is the 5th character in the unit. This means she doesn’t have to worry about tanking and can focus on healing with the occasional multi-targeting nuke to finish off the enemies after everyone else has had a row with them. In that sense, I think she works perfectly in the fifth and final slot.

The Esper Mansion is a gigantic shoutout to Phantasy Star II, since it obviously has its origins in that game. There are references galore to Lutz and even Alissa from PSI. As the group makes it towards the center of the Mansion, the next big plot development occurs. Despite Kyra’s pleas that she believes that Lutz is here in the Mansion, Rune corrects her saying he’s been dead for a while now (After all at this point Lutz would have to be over 2000 years old to be alive still). Instead, his spirits carries on in the Telepathy Ball. If the right person were to present itself at the Telepathy Ball, then all of that Lutz’ experiences and thoughts would transfer over, in this case to Rune. Because Dark Force continues to assault the Algo universe once every 1000 years, this allows for the solar system to be prepared to deal with Dark Force even many years down the road as a defense mechanism. Since Rune now has the memories of the previous generation Lutz’ he also knows why Dezolis is being bombarded by the calamity: Palma’s destruction in Phantasy Star II lead to an imbalance which seems to be the cause (that’s the assumption at least). They’re uncertain if Dark Force is still around or not, but the possibility is still up in the air. So the logical conclusion is to assault the Garuberk Tower, but the tree barricades them from doing so. The response to that is the Eclipse Torch, but those that guard it refuse to hand it over to just anyone. Unfortunately, some minions appear and steal it, with the condition that the party need visit the Air Castle to retrieve it.

I really like these scenes for the main reason it continues to drive home the “Each generation surpasses the last” theme the Phantasy Star series has always had. This keeps things consistent among the games, and gives the events in PSII more weight to them, since the major event in the 2nd half of that game was the destruction of Palma. The introduction of the Eclipse Torch further cements these connections (as is common in PSIV by now) and the Air Castle brings memories of PSI back to the seasoned PS veteran. And you know, being one of those myself that always gives me a raging fan boner. While this section might be construed as unnecessary, I disagree and in addition I think it leads to some of the more memorable sections of the 2nd half of the game.

(You know things are getting serious when the weird cloaked dudes are coming out of their cellars)

For the Air Castle itself, it’s easily the most complex dungeon in the entire game, featuring two boss fights, many alternate paths, constantly switches between inside and outside sections, and feels like a gauntlet round in a sense. So essentially it’s about as difficult as one of Phantasy Star II’s easier dungeons (Which alone says more about how unnecessarily complex PSII’s dungeons were). Of the two boss fights in the Air Castle, both are interesting in a variety of ways. First off is the power trio of Xe-A-Thoul. The most notable thing about them is that they’re the only boss fight in the entire game that has a counterattack if the player uses any multi-targeting attacks on them and that counterattack is pretty damn nasty. Beyond that is the basement which is an exact replica of the layout of the Air Castle of Phantasy Star I. Another neat reference that I certainly appreciate as well as I’m sure other PS veterans will. Especially when you take into consideration that PSIV uses an overhead perspective whereas PSI used a first-person perspective, which makes that level of attention to detail pretty incredible. At the end lies LaShiec, still somehow alive even after the thrashing Alissa handed him in PSI. One interesting detail is that the boss music for LaShiec is the same music used for Zio (Who was controlled by Dark Force), implying a link between them.

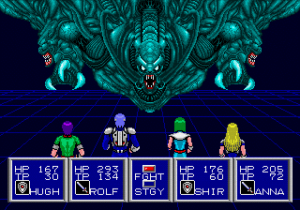

After defeating LaShiec once more, he disappears into nothingness (Apparently at the hands of Dark Force), they have the Eclipse Torch allowing the group access to the Garuberk Tower once and for all. For one thing, Garuberk Tower is absolutely nothing like PSI or PSII ever had in terms of dungeon aesthetics. It’s purely organic, in the creepiest way possible. PSII was too focused on illustrating a cold and cruel atmosphere so every dungeon in that game had to be cold and mechanical, and due to hardware limitations nothing like this could have been presented in PSI. GT is full of the most disgusting organic elements that one could come up with in a 16 bit context. Monsters heave saliva at the player, dislocated eyeballs are scattered about (And some need to be investigated in order to progress through the Tower since they lower walls that blockade other portions). The organic nature of Garuberk Tower really meshes well with Dezolis’ traditional position of having very little to do with the technology of the rest of Algol. At the top of Garuberk lays Dark Force (again?). This certainly proves the suspicions the party had before about multiple Dark Forces being true, the second one does differ a bit in how it looks (It’s a bit bigger with more spider-like legs at its sides).

What I really like about this portion of the game is the fact that most of the game has been a pretty breezy ride, but not to the point of being handholding. Its been slowly building up in terms of difficulty and now it finally peaks, throwing two of the most difficult dungeons in the game at you at once. They’re not impossible or cheap dungeons by any means (The designers probably used up all their impossible dungeon designs by the time they finished making Phantasy Star II) but still manage to put forth a very considerable challenge and that’s a sense of balance I really like and appreciate. As was the case with Phantasy Star II, the difficulty often skewed too far in the direction of sadism. There’s nothing wrong with a fair challenge, but in moderation lies the key.

With the second incarnation of Dark Force dead, Garuberk Tower disperses, saving Dezolis from all the intense weather storms it was suffering from. As a result, Kyra leaves the party having accomplished what she set out to do initially. With things at ease, all seems well until an explosion in the distance over the same Temple that refused to initially hand over the Eclipse Torch. Upon arrival, the priests there explain that they believe it to be the work of “The Profound Darkness” and mention Rykros. The next step becomes to acquire the Aero-Prism (Another PS reference!) at the Soldier’s Temple on Motavia. While they work their way back there, Demi sets up the Hydrofoil, the final vehicle in the game which allows travel across water (Meaning all of Motavia is accessible to the player at this moment).

Once the player enters the Soldier’s Temple, they’re introduced to Seth who immediately joins the party. Now, I said before that Kyra was the last 5th, and that’s still true in a sense. Once the party reaches the apex of the Soldier’s Temple and collects the Aero-Prism, Seth is revealed to be the third incarnation of Dark Force the party has had to fight (Players who have a real nose for attention to detail might notice that Seth’s skill list is full of abilities the first two Dark Forces used prior; totally not suspicious). Unlike the first two times, the third Dark Force has a full body instead of being a head attached to an entity. One interesting thing to note is that each succession of Dark Force in PSIV has more and more humanlike qualities, going so far as to have him successfully imitate one in the form of Seth. What that means in the end is up for debate, but I like to think its PSIV’s way of saying even “evil” is a living, breathing entity of its own kind, regardless of ethics.

With the Aero Prism revealing the location of Rykros, the party moves to head on to the mysterious planet unheard of until now. Once there, a spirit named Le Roof who explains that he is there to elaborate on the Genesis of Algol, but only once the group has performed a task for him to showcase their worth. Now, this part of the game seems like a fetch-quest (and to be honest, it kind of is), it serves the purpose of having the player explore through Rykros. It’s new and the player has yet to have a chance to explore through it, so at least it has the benefit of being a new and unexplored area. It helps that the items collected are actually used for the player’s benefit later on, and not just exclusively a plot item. This section of the game is only two dungeons (There’s a third but it’s inaccessible for the moment).

Once the party has accomplished the task, Le Roof explains everything about the history of Algol. The summarized version is that two ancient spirits fought each other a long time ago. The winner was declared The Great Light and the loser The Profound Darkness. In response, The Great Light sealed The Profound Darkness via a seal that included the three main planets of Algol (Motavia, Palma, Dezolis). For the most part the seal kept it away, but every one thousand years it was able to send a small portion of its soul known as Dark Force into Algol. Rykros was the invisible, fourth planet was created when the seal was at its weakest to remind Algol of its duty. Because of Palma’s destruction in Phantasy Star II, the seal is currently much weaker than it once was, and the seal is coming to its final moments. The only way to truly stop The Profound Darkness is to enter its dimension (Thanks to the items the party collected during the fetch-quest, they can do so with no harm to them). So, the goal is to go in, defeat TPD, and come home and celebrate, right?

Well, this is where PSIV changes things up a bit from how RPGs typically handle these situations. Chaz immediately resents being construed as a puppet and refuses the call to action. Hell, he even compares it to being the same as Zio – a puppet following the whims of its master. Rune has an idea on how to properly explain everything to Chaz, which lies directly in the Esper Mansion. Rune leaves Chaz alone to find the sword Elsydeon. Now, while this seems a bit generic and tame in most circumstances, this is where things get interesting. The moment Chaz receives the sword, the memories of all those before him who fought hard against Dark Force/Profound Darkness to preserve peace for the Algolian Solar System flood into his mind. The struggle against Dark Force goes far beyond just himself, but everyone around him.

Now, the player may be wondering what difference that makes from now and then. After all, Chaz is now mentally prepared to go take on The Profound Darkness, exactly what he was told to do before. To me, the difference is that Chaz has chosen to do so willingly for the benefit of those that he cares about. That’s what makes him different from the likes of Zio who did so only because he was chosen. This is what makes him different from a stereotypical “Chosen Hero” because in those situations the hero has no “choice” in their actions, everything is guided along by fate or something else. That is not so here, instead Chaz has chosen his own path for the sake of those around him. It annoys me so much to see so many video games resort to a “Chosen One” archetype to justify making a main character important or the most powerful person in the universe without building them up first. Now, it could be argued that Chaz isn’t the most developed protagonist ever but I think the game gives him a decent amount of characterization, enough even to say that this game avoids that specific trope rather well. This whole scene also continues the “the next generation surpasses the next” theme in a very vivid manner seeing as Chaz is literally experiencing the triumphs and failures of the generations that preceded him. On the subject of the Elsydeon, there’s always been a bit of controversy on it stemming from the thought that it might be the Neisword from PSII and the Laconian Sword from PSI. Considering that it’s a statue of Alissa that’s holding the sword in the cave, and he also finds memories related to those of Rolf (Who held the Neisword in PSII), I have always believed this particular theory. It’s all up to interpretation of course, but it makes everything feel like a successful closer to the final dramatic moment in PSIV, so I’m going to make the assumption that is the case.

With that settled, the group moves back to Motavia to find that all the previous party members (sans Alys, for obvious reasons) has decided to join Chaz and co. for the final battle. Of course, this being a game with technical limitations the party is only allowed to take one of them into the final battle, giving five party members for the fight against The Profound Darkness. Normally the party wouldn’t last in the dimension that The Profound Darkness exists in, but thanks to the rings that the party acquired in Rykros, they can easily survive (Which adds an in-game reason as to why only one more party member can be taken, which I guess is better than leaving it up to video game logic).

However, before I get into details about the final dungeon and the final boss fight, I’d like to speak on one last sidequest that opens up at this point. On Rykros, The Anger Tower was previously inaccessible but that it no longer the case. The dungeon is fairly similar to the other towers on Rykros, but it ends with Chaz in a one-on-one encounter with what seems to be Alys. The fight is pathetically easy, but it’s revealed to be an illusion for one of the spirits that exists in Rykros. The spirit has a question for Chaz and what happens next depends on the player’s answer. If they say “no” then they are awarded Megid, one of the most powerful techniques in the entire game. If the player answers “yes” then they are forced into a boss fight that they will surely lose unless they’ve hacked the game. Megid is powerful enough to warrant completing this sidequest no matter how badly the player just wants to finish the game.

The reason for this is that the spirit asks the player a philosophical question. Do they deliberately want and desire a very dangerous kind of power? Chaz’ rejection is based on the notion that he doesn’t want to be controlled by it. And by therefore refusing to be controlled by it (In a similar manner that he rejected taking down The Profound Darkness, I might add), he has then proven himself capable of controlling it. The person who explicitly desires this kind of dangerous power is the one who will become dominated by it, which is why doing so makes Chaz worthy of it. It’s only a small detail, but it’s also a touch I appreciate in the end. On the subject of Megid, it’s a lot more viable in this game than it was in PSII. In that game, it deducted half of the HP of all your party members in determining the damage output of Megid. Here, it’s still extremely powerful but no longer has that side-effect, so it’s okay to use it without worrying about being trashed by the next enemy you encounter. What also makes it interesting is the use of Alys, Chaz’ mentor to instigate an emotional reaction out of him, yet holds still in his convictions to make sure he makes the right choice. It’s not a huge detail but it’s one I still very much appreciate.

Finally, before the player gets a chance to tackle the final dungeon they are afforded the opportunity to take any of the previous party members that left into the final battle. They’re properly leveled and equipped automatically, so the player doesn’t need to do any tedious grinding to get them up to speed. The player also has the ability to skip choosing a 5th member to assist him or her in the final dungeon. There are no benefits for doing this outside of a player seeking a challenge. Regardless of what the player picks, the final dungeon all things considered is pretty easy. Virtually every enemy in it is weak to Holy attacks (Which the player should have an abundance of at this point). They’re all very susceptible to instant death, and with the levels the player has accumulated, they should more than enough to clear through the majority of the enemies no problem. One criticism I commonly hear regarding the final dungeon is it’s aesthetic design. Namely, the dungeon is a wild mix of sprawling colors thrown together to give an eerie and psychedelic edge. I think it works to great effect but others have complained that it made it difficult to progress through the dungeon.

At the dungeon’s conclusion, lies The Profound Darkness. The boss fight is interesting, for a variety of reasons. For one, it includes some interesting aesthetic design choices in the final boss, is split into three sections giving a dramatic final boss feel, and thematically serves as the finishing number for the Phantasy Star franchise. Each of the three forms of The Profound Darkness shares the same color as the respective Dark Force encounter, as well as their style. The Profound Darkness goes from looking inhuman, to insectoid, to finally having a human-like figure. I’m not sure what that’s exactly supposed to represent, but the fact that the designers chose to pay attention to such a minor detail entails to me that it certainly wasn’t a coincidence (or I could be playing the part of a pedantic nerd, who knows!)

As far as difficulty is concerned, the final boss I feel is a fair challenge. It certainly can dish out heavy amounts of damage and is the only boss in the game that can dispel the party’s buffs. Yet I’ve never once lost to it in all my time playing PSIV, so I don’t think it’s an over the top kind of difficulty either. What really makes the fight awesome is the music of the fight. I’ve mentioned before that I love PSIV’s soundtrack as a whole, but the finale really makes that apparent. The first two forms use a doomy, droning funeral march number to really set the mood of the battle. But where it kicks into gear is the final form into some fucking heavy metal. On the Genesis sound chip no less, which I imagine is an impressive feat (I’m no programmer, so all I can do is merely assume). The way the percussion slowly builds and builds with synthesizers adding layers of texture; leading up to the head-banging main riff alongside a very catchy bassline makes the fight seem so much more dramatic and bombastic as a result.

With The Profound Darkness finally killed once and for all, Dark Force’s influences across Algol are finished. Everyone gets together one last time to say their final goodbyes. Raja, Wren, Rika, Demi and Kyra set out on The Landale to return to their homes on Dezolis and Zelan. However, at the last second Rika decides she wants to be with Chaz and dramatically jumps out of the ship in a heartwarming moment while he catches her. Rune leaves the two alone and disappears, properly ending Phantasy Star IV. The credits roll while briefly explaining that the sacrifices of generations past are never forgotten and only serve to fuel the next generations – The principal and underlying theme of Phantasy Star IV and the series as a whole which I think is something that anyone can relate to. After all, don’t parents wish for the generation in which they’ve created grow up to supersede their accomplishments, and for that process to continue ad infinitum? That’s exactly what’s happening with players who played I, II and IV. They’ve had the opportunity to see how the Algolian solar system has developed, changed and transformed over the course of two thousand years and to see the entire civilizations that Algol has fostered to finally live in peace is a satisfying and emotional affair. This kind of accomplishment is nothing like I’d ever seen or felt in any other RPG series, which is why Phantasy Star is one of my all-time favorites.

Phantasy Star IV, at its core is a game intended to finalize the Phantasy Star franchise and bring everything to a close. All the references and nods to past games, all carefully crafted to bring about the end of the series in one powerful stroke. It’s almost customary in today’s video game industry to continue franchises well past their high points, degrading the series until it cannot sustain itself anymore. Instead, PSIV chooses to go out with a bang, much like a successful rock band retiring at the peak of their popularity instead of dragging their heels every step of the way. And for that, and that alone I salute Phantasy Star IV for doing what many other series have either failed to do or refuse to do. It is for that reason, and the many others I’ve outlined in this very long essay, that I consider Phantasy Star IV my favorite RPG of all time. And no, not even Phantasy Star III in all it’s failures, can take away from that. Would I love a fifth game in the series? Absolutely, but only under the pretense that the game would equal the level of quality seen in this game and previous entries. Otherwise, it would be nothing more than a veiled attempt at nostalgia whoring. As for the game as a whole, I think PSIV ultimately succeeds as the sum of its parts. The battle system is the most interesting and obviously the best part of the game, and the plot and characters are solid, if unspectacular and the music holds up very well. None of the other features are enough to make the game a 10/10 on its own merits, but its how the game melds each unique part together into a cohesive whole that makes this game so fantastic to me.